25 January 2024

Written by Ying Han

Thinking back to her early days as a graduate student just starting out in the UBC Interdisciplinary Studies Graduate Program, Denise recalls how she had first gotten into public scholarship without even knowing what “public scholarship” meant. Now, her academic research has become irrevocably intertwined with and perhaps even superseded by the connections she has made within a boundless community—one located in Vancouver, Burnaby, Chinatown, in transpacific movement and underrepresented stories—for the better.

Thinking back to her early days as a graduate student just starting out in the UBC Interdisciplinary Studies Graduate Program, Denise recalls how she had first gotten into public scholarship without even knowing what “public scholarship” meant. Now, her academic research has become irrevocably intertwined with and perhaps even superseded by the connections she has made within a boundless community—one located in Vancouver, Burnaby, Chinatown, in transpacific movement and underrepresented stories—for the better.

From her first job working for an architect who designs museum exhibits, to finishing up a PhD built on this work, serving as research director of UBC’s Initiative for Student Teaching and Research in Chinese Canadian studies (INSTRCC), and embarking on her new role as a curator with the Museum of Vancouver (MOV)—in a way, she fondly remarks, Denise has come full circle. What powers each of her projects is a profound joy in co-creating knowledge and a commitment towards reciprocity. This has been exemplified by two award-winning history exhibitions: “Across the Pacific” with the Burnaby Village Museum and “A Seat at the Table” with the MOV and the Chinese Canadian Museum of BC.

Explore a virtual tour of “A Seat at the Table” at the MOV here. Courtesy of the Museum of Vancouver.

Winning the PHH Public Engagement Award in 2023, her nominator writes:

“By amplifying the dynamic cultural life of racialized and marginal communities through the intensification of community curated activities in situ (“in the streets”, in homes and in the community), rather than their objectification into artefacts of display in dead museum spaces, Denise is at the forefront of innovative anti-racist and inclusive practices that unsettle and, hopefully, drive forward the reform of colonial museum structures.”

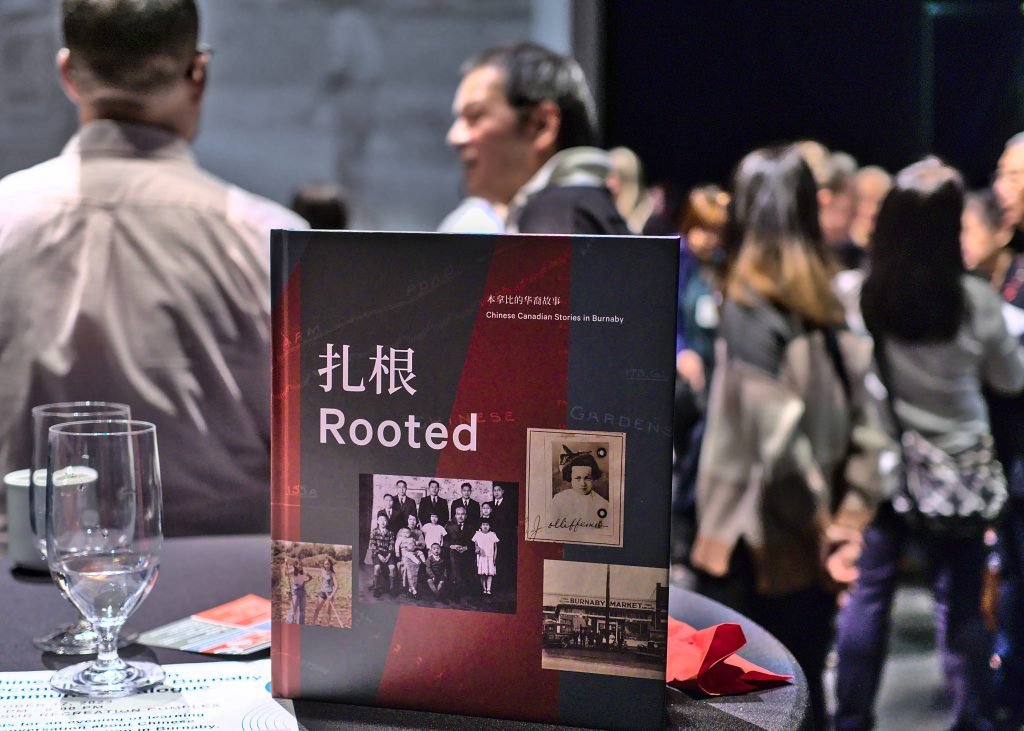

Book Launch event for Rooted: Chinese Canadian Stories in Burnaby at Shadbolt Centre for the Arts. Photo by Eric Damer.

Her most recent project, Rooted: Chinese Canadian stories in Burnaby (published 2023), was born from a collaboration with a team of heritage planners and curators at the City of Burnaby, and a shared passion about community histories. Through a collection of stories, interviews, and photographs, Rooted speaks of multigenerational perspectives spanning the late 1800s to the present day. Uplifting the voices of those who have experienced systemic oppression, this book celebrates the diversity and resilience of the Chinese Canadian community in Burnaby.

I met with Denise one late afternoon in December over Zoom. As she reflected on her now extensive experience in public scholarship, she talked with a quiet sense of conviction that spoke loudly of her dedication to this work. Denise shared stories from her most recent project, how she came to it, and the ways in which it has informed how, beyond any one specific migrant community, she approaches place-based storytelling as a whole.

The following interview is based on a transcript that has been edited for clarity and length.

Ying Han: Hearkening back to your Public Scholars Initiative profile, I’ll start by asking, how would you define what public scholarship means to you now? Has your definition changed over the course of your work, or has it remained surprisingly consistent?

Denise Fong: I would say my role in and view on public scholarship has been very much evolving. One of my first jobs at UBC was working on a public education project with Dr. Henry Yu (UBC History). It showed me how academic research can be used to contribute to public knowledge and promote change in institutions involved in cultural heritage or history work.

Since stepping outside of the UBC box, my current role at the MOV has given me a different perspective on the significance of public scholarship. What I see now is, public scholarship really helps drive activism in the community. My focus has become highlighting historical injustices, representing the underrepresented, and capacity-building—whether in supporting community organizations, individuals, or bringing students onto these projects, so that they also get an opportunity to create their own pathway.

Public scholarship is a meaningful opportunity to co-create knowledge across many sectors: universities, the broader academic community, cultural institutions, community groups, industry. There are many ways in which doing this work has also changed how I see myself, in my own sense of awareness of the world and of my identity as a Chinese Canadian public scholar and museum curator.

Read Denise’s BCMA Roundup magazine article “Unlearning the Museum in the Time of COVID-19”

YH: You’ve mentioned all these different bodies that can be involved in “scholarship” together, with the industry, different disciplines, and community members. I wonder then, how would you define the “public” in public scholarship?

DF: What we are often used to in academia are big concepts, big ideas—and there is value in finding ways to be informed by some of the theoretical work that is happening within academic circles. But, in the past decade or so I’ve worked very closely, directly, and intimately in community with elders, business owners, organizers, families, and individuals.

In that sense, the public is not an abstracted concept. For me, it is really about the people that I have come to know and gotten to work with over the years. Their sense of what is important helps shape the work that I am trying to do. In the teams that I have been involved—in research, heritage planning, or museum work—we all try to collectively uphold and sustain those relationships in a very respectful and reciprocal way, as we do this work of addressing historical injustice and when thinking about the underrepresentation of communities in general.

Denise Fong delivering a Mandarin guided tour of the A Seat at the Table exhibition at Museum of Vancouver. Photo by Henry Yu.

YH: Thinking of your earlier experiences as a grad student working with Dr. Yu, could you talk a little bit about maybe some challenges you faced on this path to public scholarship, especially as a grad student?

DF: As a graduate student, I have had to unlearn colonial structures that can get in the way of how we address community needs and respect their timelines and comfort levels. I started off as a project manager; with that more administrative position, my role was to make sure the project was done according to institutional rubrics based on efficiency, on a certain timeline, on budget. This outlook tends to drive how we (de)value people’s needs in these processes.

Time management is especially challenging when working in communities as a student, with part time jobs and other responsibilities. You cannot step away from community work the way you can step away from a more admin or routine job. With community work, you want to always remain available and connected, but community demands can conflict with other schedules in your life. I have had to learn how to navigate and balance different priorities.

I am also working as a racialized early career scholar and in a very interdisciplinary space, along the margins of many different interconnected or closely related sectors and communities. Every discipline—and community—has its own sets of knowledge, language. I am grateful to work in this interdisciplinary manner; I have benefited a lot from this training. But it also means I must be very quick at switching contexts and learning new ways of thinking and presenting ideas. So, while it is a good challenge, it is still a challenge.

YH: Projects like Chinatown Reimagined seem like one very explicit way of reaching out to the community, and seeing and hearing this wide range of community actors say exactly what they want to research and to be researched. Could you talk a bit more about your process when it comes to identifying community needs?

DF: With Chinatown Reimagined, a lot of it comes from the long relationships that my research supervisor, Dr. Henry Yu, has had with the Chinese Canadian communities connected to Vancouver’s Chinatown, and to other organizations leading the work of heritage conservation and envisioning futures for Chinatown. This also needs to be contextualized within the last few years given the rise in anti-Asian racism with COVID and the many layers of challenges it has posed for these neighborhoods. I have learned a lot from Dr. Yu and other community leaders who have been committed to building a sense of trust within all these different relationships.

More concretely, there are techniques we incorporate to make academic research more accessible to a wider audience—like presenting exhibits in different languages and plain language or facilitating programming where students and community members can collaborate outside of the UBC campus. But really, the foundation is having that ongoing commitment to communities and recognizing that everyone is coming from very different perspectives. Other public humanities scholars have also talked about the importance of relationality in their work, and the ways in which it informs their awareness of how communities want to be engaged in different processes, and how to create opportunities that meet the needs of communities.

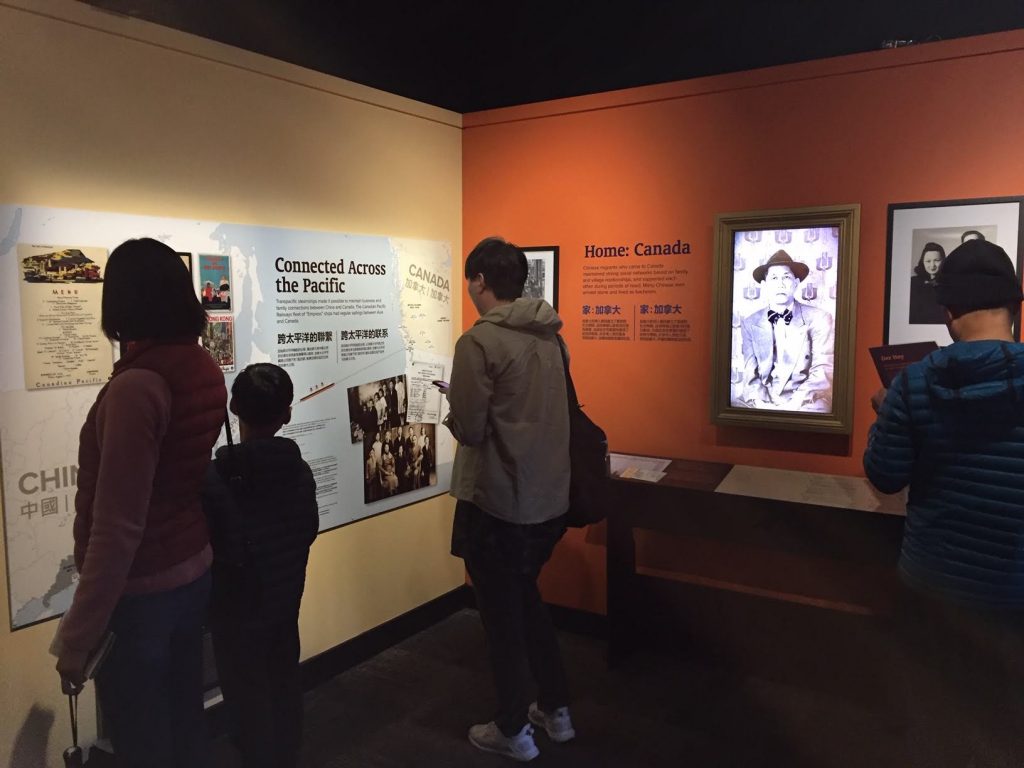

Artifact display inside the “Across the Pacific” exhibition at Burnaby Village Museum. Photo by Denise Fong

One of the benefits of the university is that we have access to funding, resources, and staffing to help support this kind of community building work, that oftentimes local organizations, or nonprofits, or individual activists cannot access. It is truly wonderful to have these ongoing relationships where we can leverage resources on campus but also be able to bring in the expertise, the knowledge, and the passion from community to raise greater awareness about these issues.

Read more in 1923: Challenging Racisms Past and Present“

Denise’s interview with 1923 co-author Dr. Sharanjit Kaur Sandhra on The Early Edition with Stephen Quinn

Read more in Challenging Racist British Columbia: 150 Years and Counting“

YH: How do you communicate to a community the idea that they or their shared history, culture, should be researched at all?

DF: Because of the colonial history of museums, oftentimes they are considered a space for authoritative knowledge production; curators create the knowledge, defining what is important and valuable, and then “educate” or entertain the public. Museums are now recognizing that history and shifting away from it. They see the need to broaden their representation to include missing voices. For instance, there are not that many items in museum collections that reflect the diasporic migration waves of Asian Canadians.

Visitors inside the “Across the Pacific” Exhibition at Burnaby Village Museum. Photo by Denise Fong.

There is also a tendency for communities to not really perceive themselves as having a role in reshaping how museums should look like. But as younger generations of Asian Canadians increasingly work to reclaim their heritage identities and see the missing representation across different sectors and industries, there has also been more pushback against these practices that museums have had for many decades.

An important factor in connecting with communities is initiating that relationship at a very individual level. Often, when I reach out to community members to be part of museum-led projects, they are unsure or suspicious; they might not immediately understand why we want to highlight their story in an exhibit or book. Working in academia has made us hyperaware of the historical trauma that many racialized, migrant communities have faced; in reality, it can be difficult for them to bring up these family histories or want to publicly share them. It takes hard work to build those relationships over time. In the projects that I worked on in Burnaby, this was a seven-year process.

BCMA panel “Beyond the Black Squares: A Meaningful Conversation on Museums and Allyship”

Listen to Denise expound upon ideas around trauma-informed methodologies and reciprocity, and share anecdotes in the following videos. For transcripts, please watch the videos on YouTube, and click on the description box to choose the “Show transcript” option.

YH: With your point on respecting how traumatic these histories can be—this makes me think of a webinar series we just did on trauma-informed research. I’m wondering if that’s a term that, as a historian or curator, you use? What does the methodology for this kind of research look like in your work?

YH: Going back to an idea you mentioned earlier about funding and resources available in the academy that can be leveraged—could you talk a little bit more about what reciprocity means to you, or what it looks like in your projects?

YH: With this idea of co-producing knowledge, could you talk about how you develop a definition of collaboration in these different projects?

DF: The first thing that comes to mind for me is recognizing that the co-creation of our work has a significant personal impact on the individuals who are part of the project, and creating something that they are proud of, that honors these stories of how their families overcame discrimination and hardship, with perseverance and resilience. These are all important values for migrant families who have come in the early years and have faced a lot of challenges in integrating into Canadian society, as well as finding a pathway or a way of living to support their families. If the research can address some of this trauma that their families have experienced, it makes the piece much more relevant and valuable in thinking about why we do this work and what we hope to achieve.

Visitor interacting with projection display at the “A Seat at the Table” exhibition at the MOV. Photo by Denise Fong.

With “A Seat at the Table,” I have heard from many visitors who have been appreciative of seeing themselves, a slice of their lives, a piece of their identities, being reflected in this kind of museum space. This also extends to artists who have not had the same kind of visibility as other mainstream or more prestigious ones. That is what should continue to drive the work that we do with communities: how can we find ways to provide opportunities, to build that capacity so that the stories of underrepresented communities can be publicly showcased in respectful ways?

YH: How did Rooted come together?

DF: When I first started with the Burnaby Village Museum, they had just begun conceptualizing this community stories project. The idea was to broaden the definition of Burnaby’s heritage, so that it would not just focus on the stories of white settlers but also be able to capture the stories of racialized communities. We have a wonderful team of heritage planners and curators at the City of Burnaby who are very passionate and dedicated allies to this work. For the most part, heritage planning and museum work is still fairly dominated by white heritage workers, cultural workers. It is important to have good allies who are in positions of power and willing to lead the work in finding, funding, and creating opportunities for this work to be done.

One of the areas I first got involved in was on documenting Chinese Canadian community history. I started to connect with the people there, and we had a few members on our advisory committee who were enthusiastic about introducing us to others. Slowly we built a reputation in the community as the fruits of their support came to life: first an exhibition and some backyard garden events, then releasing publications and public programs. I think that helped people to see how they could play a role in this kind of work.

By the time I started working on Rooted, we had this network of people who were aware that the museum or the city was doing this work, which allowed me to connect with more people. Ultimately, we featured twenty-six families and organizations in Burnaby. It was so helpful to be able to say, “I know this person, so I’m reaching out to you,” or, “this is how I found your story, would you be interested?” People have been pleasantly surprised—also appreciative of the opportunity to share their family stories.

The book is focused on some of the foundational work from the “Across the Pacific” exhibition during the pandemic, which was more focused on the farming communities in Burnaby. We were able to expand the narrative with corner stores and grocery stores, restaurants, and different kinds of religious organizations and activist organizations that serve and support Chinese Canadians and others in the Burnaby community. A lot of them are related to food, because food is such a wonderful subject that a lot of folks, whether they are Chinese Canadian or not, will gravitate towards and can relate to and find interest in.

The city is currently now also working a lot with South Asian communities. There has been this ripple effect where we start with one community, and from there, we have built a set of practices that shows everyone this is possible. This is what we can do, and this is why it is important.

Keep an eye out in the coming months for an exhibit she is currently working on at the Museum of Vancouver, which centers the work of an artist from Taiwan who documents what are called “mosquito halls” in Taiwan, which are public spaces that have been basically disused or left abandoned. UBC students will also be involved in activating this exhibition and connecting it to local stories and content in Vancouver. In May 2024, as part of the new ResiStories program co-hosted by the MOV and PHH, we will host a “lunch and learn” community event in the museum with the artist, Yao Jui-Chung.