8 August 2022

Written by Heidi Rennert

As an artist, activist, and academic, David Ng is used to falling outside neat categories. His artistic and research practices, which tackle these very boundaries head-on, extend across several overlapping roles: PhD Candidate at UBC’s Social Justice Institute, co-Artistic Director of Love Intersections, co-founder of the Vancouver Artist Labour Union Co-operative (VALU CO-OP), filmmaker, artist, and community organizer. Relationality, he says, is integral to the way he bridges these multiple roles.

Ng’s art and activism are inseparable from his scholarship. As part of GRSJ’s Creative Social Justice Studies stream, Ng’s research combines artistic practice and traditional research to imagine ways that intersectional identities can be expressed through the media arts. His research is informed by his extensive background in artistic and activist projects and organizations, a few of which feature in the following interview.

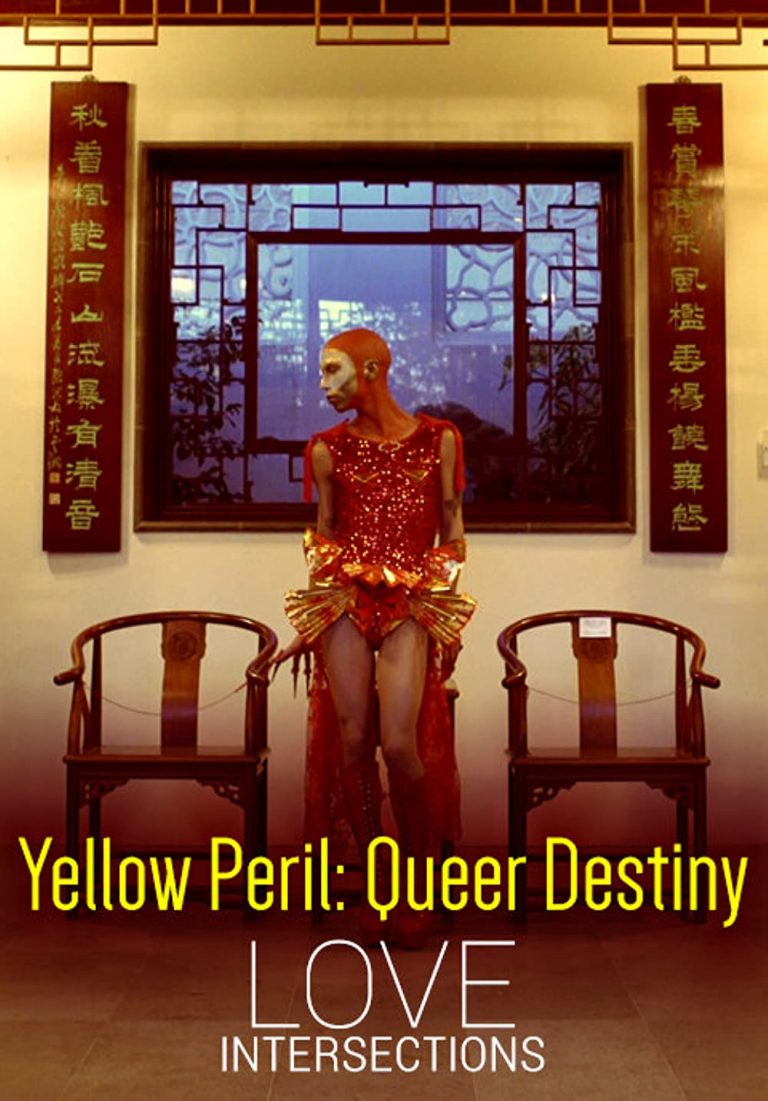

Poster for “Yellow Peril: Queer Destiny”

Co-founded with Jen Sungshine in 2014, Love Intersections is a media arts collective of queer artists of colour with a mandate to share intersectional and intergenerational stories of queer, trans and intersex, Black and Indigenous people of colour in our community. In 2019, Ng co-directed “Yellow Peril: Queer Destiny,” a documentary film that screened at over 40 film festivals worldwide and is included in BC’s curriculum on issues of gender and sexuality. Ng has spearheaded other projects, including the 6×6 “Finding Untold Stories” series, a talk show series Hot Pot Talks, and an upcoming two-day immersive storytelling exhibit with the Lim Sai Hor Kow Mock Benevolent Association (September 10-11, 2022). This exhibit, titled The House of Nine Dragons, is possible through collaboration with Ng’s work at VALU CO-OP, a unionized artist collective based in Vancouver’s Chinatown with a mandate to work on projects that serve community needs.

Ng is the graduate student recipient of the Public Humanities Hub’s 2022 Public Engagement Award, an award that recognizes exceptional public engagement at UBC. Ng’s nominators describe him as “an exemplary PhD candidate not because of individual genius, but precisely because he approaches his work in relationship to broader publics, especially marginalized communities, and he aligns his work with collective social justice values of accountability, partnership, anti-oppression and decolonization.”

In the following interview, Ng describes his trajectory as an artist and academic and how he sees relationality as fundamental to his approach to art, activism, and academia.

The following interview is based on a transcript that has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Heidi Rennert: Can you describe how you came to public scholarship? I’m especially interested in what this pathway looks like for a graduate student.

David Ng: You know, it’s interesting, I came to public scholarship sort of in reverse: I went up to the institution, even though public scholarship is often thought of as what comes [down] from the institution into the public.

With Love Intersections, a lot of what we’ve been doing over the past eight years has been grassroots knowledge production through artistic practice, particularly through filmmaking. When I started the PhD a couple years ago, I started thinking through some of the language of academia and theorizing about how it is operating in the community.

So, I see academia in my public scholarship in reverse– the work that we’re doing in collaboration with the community has always been a type of scholarship and knowledge production. The academy in many ways is catching up to and making legible this type of work.

And to touch on the social practice aspect: at Love Intersections, we primarily make films but, through my dissertation and research, I’ve been looking at public scholarship from a social practice lens [and] the artists who use relationships and social situations as their main practice or medium of practice, because a lot of the main focus of our work at Love Intersections is relationship building. We really focus on process versus outcome and what comes out of that process-based work. The artistic outputs–whether they be films or installation or artwork–are perhaps 15 to 20% of what we actually do. A lot of the work is actually this type of community facilitation, partnership, and collaboration.

HR: As someone who first started in art and activism and then later entered the academy, what does public scholarship mean to you? How would you define it?

DN: That’s a good question. I say this as someone who is receiving this award, but, you know, I’m not outside of what the institution calls “public scholarship”. Public scholarship to me sounds like a level of accountability that the institution should have to communities, right? If we’re not doing public scholarship, then what are we doing? That’s what comes to me as an activist.

As part of my research, I’m hoping to interrogate those distinctions between what is knowledge production, art, and social practice versus a non-social practice and all of those distinctions that are bound up in the dynamics of power and economy. Those things are really fundamental to the sort of anti-oppression work that I’m trying to do both with my research and with Love Intersections.

As I mentioned before, I would relate public scholarship to accountability and relationships: the relationships between me, as an academic and an artist, and to the communities that I hope I am responsible or accountable to. It’s another way that I hope to interrogate those delineations or boundaries between scholarship, public, community, art, activism.

HR: What projects are you currently involved in? How would you describe your practices more broadly across these various projects?

DN: This is still in flux. The broad picture of what I’m hoping to look at is grounded in the work of when we started Love Intersections and thinking about the possibilities of doing community, collaborative, grassroots anti-racist types of artwork. How can we change what is legible, in terms of social change or an arts practice?

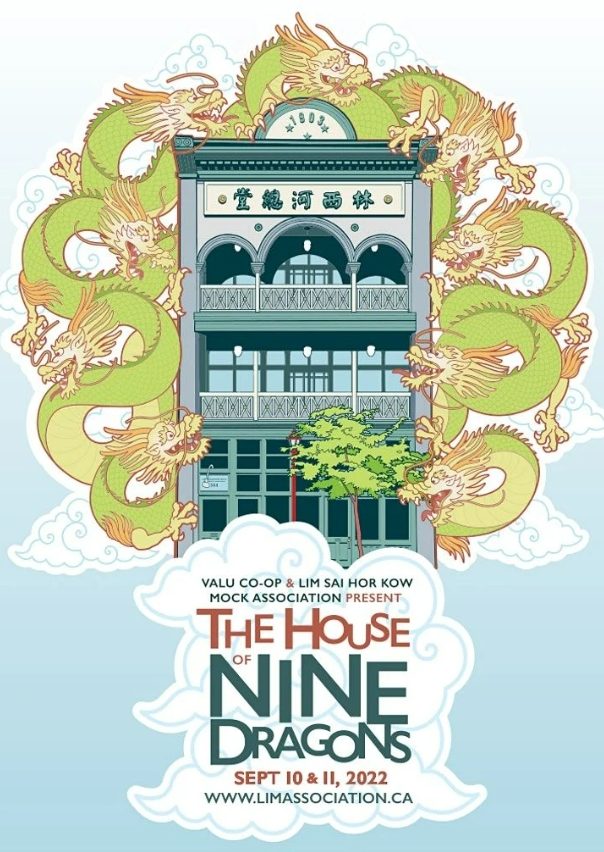

Poster for “House of the Nine Dragons” for Sept 10 & 11 at the Lim Sai Hor Kow Mock Association

I’ll give you another example in terms of arts practice. The City of Vancouver has recently started recognizing what they’re calling “intangible arts practices.” I’m not really fully comfortable with that term but I also recognize all the different types of cultural production that happen that don’t necessarily have a transactional or commodifiable output. It’s why I emphasize the social practice work that we do. I’m interested in all the ways that Love Intersections has tried to navigate arts funding spaces, academic spaces, spaces that sort of bump up against but don’t fall into the category of “intangible arts practices”. Our group is doing something under these categories and all the systems that don’t fully capture our type of work, particularly in my arena around BIPOC arts practices.

I’m involved in a number of projects and the reason why they’ve been in flux is because we do such community collaborative work. One particular project is–finger’s crossed–finally going to happen after being cancelled

three times because of COVID. We [at VALU CO-OP] have been collaborating with the Lim Association to digitize their archives and create a website and it’s building up into an exhibit called The House of Nine Dragons. That name comes from an oral history we’ve recorded with the elders at the Lim Association. The Lim Association historically is a benevolent association. These family clan organizations brought over labourers to work on the railroad so, in that particular context, we’re thinking about the role of indentured labour participating or contributing to the colonial project and the ways that system of model minority migration for the colonial project continues to persist today.

That’s just one example of a project that will likely be a chapter in my dissertation under the broader umbrella of collaboration. Love Intersections has also been looking at a series of public engagement pieces. One in particular is a talk show series we have called Hot Pot Talks, which happened during the first cancellations of the House of the Nine Dragons exhibit. Despite having to postpone the exhibit, we wanted to continue these conversations around systemic racism, colonialism, Chinatown’s food cultures, art, and activism. So Hot Pot Talks formed as a way to continue this type of public scholarship for public engagement around some of the things that were coming up as we were collaborating with the Lim Association.

HR: How does facing various institutional deadlines (like completing a chapter or meeting a funding deadline) affect your approach to community partnerships? How do you deal with the sometimes contradictory demands of the academy and the community?

DN: This is something I’m bumping up against right now. Omicron really has complicated this. We’re working with elders, and old buildings have no ventilation, so I have to deal with ethics.

This type of deep relationality enters a sort of complicated ethical field, ultimately, because of research reasons, but also because the institution has ways of dealing with liability and whatnot.

I had a conversation with a former GRSJ doctoral student Jules Koostachin and she called it “a statement of relations.” I really love recognizing the interconnectedness of our work and going back to accountability and relationships. Those are deep, deep ways that social justice activists are thinking about. We’re not talking about “object objectivity” but the opposite of that: really deep relationality and accountability.

Promotional poster for Season 3 of “Hot Pot Talks”

HR: I like that. Along these lines, how do you approach challenges with community partners?

DN: This was compounded by COVID, but I found that organizing and the relationship piece have to happen together. There’s a great quotation, which I will quote to my grave: “Relationships move at the speed of trust.” So, cultivating that trust aspect takes time and it’s hard to do over Zoom.

Recognizing that key point has put things into context for me. When I get frustrated when things don’t start organizing quick enough, I realize, do we need to sit down and have a coffee or have dinner or do something? You know, something relationship building? And that’s sometimes so antithetical to the way that academic timelines and deadlines work. In the activism world, we can have all of the social justice language and have all the intentions about contending with power, but things really fall apart if we don’t also think about the relationship and trust-building piece.

HR: Was there anything you learned through your collaborations?

DN: A core philosophy of Love Intersections is doing work by invitation. We don’t parachute into communities and say, “Hey, queer South Asian deaf community!” Invitations happen sometimes by a cold email. When [our collaborator] Amar Mangat first emailed us, he was like, “Hey, I heard you guys are doing this work. Have you ever thought of making a film about a queer South Asian person?” And so we’ve done several collaborations with him.

Invitations will happen that way, but they will also happen by forming relationships with community members, hearing what stories they want told, and then building partnerships from there.

HR: How do you see your critical and artistic work informing each other? In what ways does your artistic practice affect your dissertation and research, or the other way around?

DN: I’ve been thinking about this accountability piece because [my supervisor and I] just finished writing a book chapter on ethics and storytelling. I was really inspired by Indigenous scholar Shawn Wilson’s Research is Ceremony. Each chapter opens with a letter to his children. He infuses the biographies or stories of his supervisory committee into his dissertation [and published book].

Wilson is thinking about statements of relations, this idea of “my” knowledge and the formation of my dissertation that comes through this network that I’m trying to be accountable for. It’s not my own work. As an artist, I also bump up against this. Arts funders want sole authorship and academia also pushes for that. Jen [Sungshine] isn’t doing her PhD but this is her work, too, right?

I’m going to a film festival at the end of August and the Canada Council for the Arts is asking me, “Well, who’s the director? Who’s giving you funding? Do they own the work?” We’ve always wanted to centre the ownership of the work in community. We sometimes have five co-directors because we all want to flatten who owns what, who’s making the decisions.

HR: What kind of impact do you imagine having with this project? What kind of responses are you hoping for?

DN: I’ve been thinking, particularly with the Lim Association, that when we invite people to learn about Chinatown and see the exhibit, I really hope they see their own connection to the systemic stuff I’m mentioning. It’s not just the story of the Lim Association, it’s not just the story of Vancouver’s Chinatown; it’s the story of all of us as mostly settler Canadians engaging with this type of neighborhood. In our Love Intersections films, I not only want to talk about homophobia and intersectionality; I also want to connect with people who are outside the identities that are in the films. Obviously, I want people to learn. But I’m also thinking: how do we get people to not just learn but feel differently and connect to these stories?

The House of Nine Dragons will happen on September 10 – 11, 2022. Event registration is free and open to the public.

David Ng is a queer, feminist, media artist, and co-Artistic Director of Love Intersections – an arts collective made up of queer people of colour. He is currently a PhD candidate at UBC’s Social Justice Institute, and holds a Master of Social Sciences from the African Gender Institute at the University of Cape Town.

David Ng is a queer, feminist, media artist, and co-Artistic Director of Love Intersections – an arts collective made up of queer people of colour. He is currently a PhD candidate at UBC’s Social Justice Institute, and holds a Master of Social Sciences from the African Gender Institute at the University of Cape Town.