25 October 2022

If students are looking for a fun language learning opportunity, Dr. Maria Carbonetti (FHIS) warns, Spanish for Community (SFC) might not be not for them. Joining one of its many translation projects often demands a commitment that extends well beyond the deadlines of a semester. Students trade summers abroad for long hours at their desks translating materials about public health policies, citizenship courses, or fair trade coffee houses.

Yet students are continually drawn to this work, a fact that Carbonetti believes speaks to their larger desire to connect their learning with real-world contexts. SFC’s model gives students a valuable opportunity to move beyond language textbooks and learn Spanish by engaging with the community.

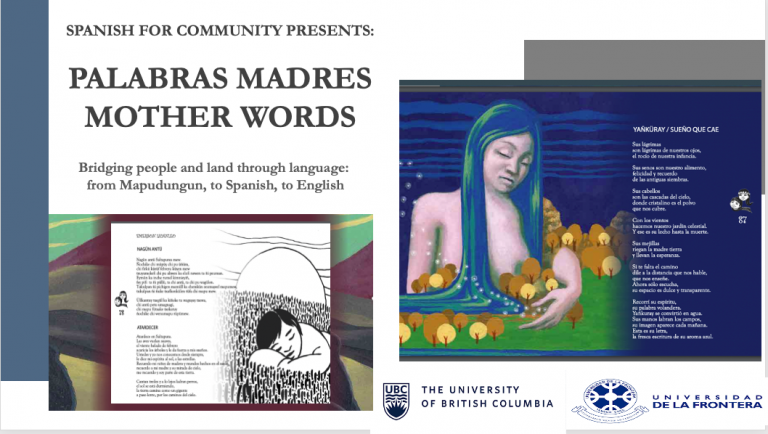

In her latest project, Palabres Madres, Carbonetti and Spanish 301 students collaborated with Dr. Carolina Navarette from Chile’s University of Universidad de la Frontera to examine the role of Spanish literature, translation, and language learning in sites of settler-occupied Indigenous territories. In examining the roles of colonialism and language revitalization, the class produced bilingual translations of Mapuche poetry and literature and met with Musqueam artist and knowledge keeper Deborah Sparrow.

Carbonetti was awarded a Public Humanities Hub Public Engagement Award in 2022 for her ongoing work with SFC and her model of community-engaged learning. In the following interview, she shares the origins of SFC and her approach to community-engaged language learning.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

What led you to public scholarship, community-engaged teaching, and the founding of Spanish for Community?

Maria Carbonetti: I’ve been engaged in public humanities since my undergraduate studies in Sociolinguistics. I’m from Argentina and was working with Mennonites who immigrated to Argentina in the 1980s. Not only was I researching their linguistic backgrounds (they were from Mexico and spoke an old form of German) but I also ended up helping them manage issues with the provincial government.

When I started teaching languages, it had been my intention to connect students with the reality of a language’s power and culture. Particularly at the beginning stages of language learning, I wanted to bypass cultural stereotypes that one normally finds in books for second language acquisition.

I learned so much about how students can thrive when you give them a challenge that seems really big. But it’s possible because they know why they’re doing it and they are interacting not only with organizations partnering with us but also, most importantly, with people who will benefit from the work, learning from them directly.

Later, I began working with intermediate and advanced students. I had the opportunity to invite members of the Hispanic community into our classes, particularly refugees and asylum seekers. I started bit by bit working with neighbourhood houses on little projects before moving towards larger projects. For example, I asked my students if they were interested in translating materials for citizenship courses, because these were needed by neighbourhood houses in Metro Vancouver. They said yes, but their language ability wasn’t high, so we had to craft that process. I learned so much about how students can thrive when you give them a challenge that seems really big. But it’s possible because they know why they’re doing it and they are interacting not only with organizations partnering with us but also, most importantly, with people who will benefit from the work, learning from them directly.

More projects and people and agencies began to approach me and ask, “Could you do this for us? Could you do that?” And then we began to expand our projects locally and abroad in Central and South America.

Our first international project was with the Comite Campesino del Altiplano, which was at that point the largest Indigenous organization in Guatemala. They are now a political party and run a network of businesses for coffee, sugar, education projects and other things. They were trying to sell their fair trade coffee and gave us documents to translate into English.

The Geography department invited the leaders to UBC, and fortunately our students had the opportunity to meet with them in person, to hear them and to ask questions. We were basically learning first-hand from them. Reciprocity and co-teaching with our partners are key in the SFC model. Language learning education in North America sometimes presents language and culture in stereotypical ways. So it was very interesting to have these leaders with us. It was eye-opening to learn how much we can accomplish through these kinds of partnerships.

These projects were the seed of Spanish for Community.

These projects seem to offer students an opportunity to learn a language through translation while also engaging with contemporary, political issues. Their language learning can have real world impacts.

MC: Yes, I try to bring themes of inclusion, diversity, social justice, and public health into each course I teach. For Palabras Madre/Mother Words, we focused on the indigenization of second-language learning, especially considering that Spanish is a quintessential colonial language that brings this major path to student experiences.

Spanish for Community allowed me to formalize and create a dedicated space as an initiative for community engagement for Spanish teaching and learning, to create, develop, coordinate and house different projects and also different modalities for different Spanish courses in our department.

There are projects suitable for conversational classes, projects for intermediate or advanced students, projects for a translation class. At the same time, Spanish for Community makes space for students who aren’t taking courses but who want to volunteer or be fellows in the program. They can join a specific project or play some role in the course-based projects.

In this way, Spanish for Community is like an umbrella: it offers different models of community engagement.

Our projects are very real and relevant, from both the community service point of view and the academic point of view. Reciprocity is very important. I ask partners: “Do you really need this?” They need to explain to me why they want our help and they need to connect with our students and collaborate as co-teachers. I want students to know why we are doing this work, and why it is valuable for their learning journey.

How do you develop your partnerships? How often are you approached with projects, and how often do you seek out or develop work with new or existing partners?

MC: I’ve developed projects in different ways. For example, we typically begin international projects through contacts with colleagues or former students. The co-coordinator for Palabres Madre, Dr. Carolina Navarette, lives in the University of De La Frontera in Chile. She completed a postdoctoral fellowship here and was one of the first people to work for Spanish for Community as a community liaison. We had talked about how we both were teaching in institutions in Indigenous territories, in colonial languages, and on topics in literature. When we conceived this project, we didn’t yet know exactly how it would look but we wanted to start making connections. We wanted to build this transnational relationship between the North and the South West Coasts that would respond not only to a colonial language, but to the colonial way of teaching and learning a language. We had the fortune to bring on board the poet and activist Mapuche Indigenous leader Jacqueline Kenny, who is an awesome scholar. And then a partnership began.

In other cases, community partners such as the neighbourhood houses have approached me. It’s fantastic when this happens. The Centre for Community Engaged Learning also helps to make those connections and to support instructors and students with tailored training sessions and resources.

In Spanish for Community, I don’t have an idea of a project and then impose or sell it to the partners–it’s the opposite: we try to respond to a specific need coming from the community while considering rigorously specific course objectives and learning outcomes. We try to be as faithful as possible regarding what our partners really need and what the program curriculum asks for. Our projects are very real and relevant, from both the community service point of view and the academic point of view. Reciprocity is very important. I ask partners: “Do you really need this?” They need to explain to me why they want our help and they need to connect with our students and collaborate as co-teachers. I want students to know why we are doing this work, and why it is valuable for their learning journey.

How do you measure the success of a project, or evaluate your students, when you’re dealing with these different timelines? How do you know when a project is complete, even after the semester has ended?

MC: Usually a project has two endings:

One ending is in regards to the students, goals, and learning objectives that fall within the semester, which we need to evaluate according to a timeline. I want each project to be integrated in everything that we do, language and communicative skills (listening, speaking, writing, reading) as well as intercultural awareness. If we read a short story, I choose one connected to a project’s themes. I don’t want them to feel that our project is a compartmentalized part of the course. Everything is integrated.

The other ending is Spanish for Community’s promise to meet its deliverables for our partners in for example, translation-based projects. This involves more work after each semester, because we want partners and students to meet again and acknowledge the work in some kind of celebration. This is not a study abroad where you have all the fun. This is serious work and the students mostly work in class or at home. It’s a very disciplined sort of language learning. We have a lot of fun, but it’s not the same as traveling to Peru.

This is why it’s important to really prepare the terrain for students to be convinced about what we’re doing. Every project is different, every partner-student relationship is different. It’s always uncharted territory.

What common challenges do you encounter with this kind of work?

MC: There are several answers to these questions. Designing each project tends to be challenging for different reasons. Managing the volume of the work and the needs of partners is challenging, because our partners have their own problems and timelines. I have worked with Latin American grass roots organization, with refugees, with the Vancouver Association for Torture Survivors. They have problems that are way larger than the problems of a very privileged Spanish class at UBC.

The other part is evaluation: to be fair with the students while providing a good quality product for the partner. We also want to make the students feel safe about taking risks. Instructors need to discuss with students how to be at ease with risk.

Another challenge is to make the university structure understand this model. This model is very much like water; it’s difficult to frame or replicate year after year and with the same partners. As a lecturer, it’s very complicated to advocate for more dedicated time, to negotiate teaching loads, or funding, in order to make this work sustainable in the long run. In recent years, there have been significant advances in terms of support in my unit but it is still a work in progress. Nevertheless, I’m convinced that we’re providing great opportunities for students, so we will keep doing it.

What does “public humanities” mean to you?

For me, community engagement is always public humanities. Teaching languages is about dialogue and conversation and sharing knowledge, particularly with our larger community.

I really like Paolo Freire’s description: “Knowledge emerges only through invention and reinvention, through the restless, impatient, continuing, hopeful inquiry human beings pursue in the world, with the world, and with each other.”

I think this is the connection between language learning and the public humanities: that we learn through constant conversation, through which we create more understanding and knowledge that is relevant for students and relevant for the world that we live in. If not, why take a language course? Why not just learn by ourselves? The students miss so much if they do not engage with the public.

Dr. María Carbonetti is a lecturer in the Department of French, Hispanic & Italian Studies (FHIS) who has developed advanced language and culture curriculum for the Spanish Program at the University of British Columbia. Carbonetti is a director of Spanish for Community, a community-based experiential learning initiative at the FHIS she created in 2016. Her research is currently focused on community engaged learning pedagogies applied to second language teaching and learning, particularly on translation as intercultural mediation in relationship with diversity, inclusion and curriculum indigenization/decolonization practices. She was the recipient of the Killam Teaching Prize in 2019 and the recipient of a Public Humanities Hub Public Engagement Award in 2022.

Dr. María Carbonetti is a lecturer in the Department of French, Hispanic & Italian Studies (FHIS) who has developed advanced language and culture curriculum for the Spanish Program at the University of British Columbia. Carbonetti is a director of Spanish for Community, a community-based experiential learning initiative at the FHIS she created in 2016. Her research is currently focused on community engaged learning pedagogies applied to second language teaching and learning, particularly on translation as intercultural mediation in relationship with diversity, inclusion and curriculum indigenization/decolonization practices. She was the recipient of the Killam Teaching Prize in 2019 and the recipient of a Public Humanities Hub Public Engagement Award in 2022.