3 April 2024

Written by Ying Han

When asked what he would rate as the best legal drama, Professor Etxabe’s most recent recommendation is Anatomy of a Fall (2023, dir. Justine Triet), but his favourite of all time is still its predecessor, the American courtroom drama classic, Anatomy of a Murder (1959, dir. Otto Preminger). What makes them so interesting, he explains, is how these films are multi-layered in their approach towards depicting difficult, complicated subjects; there is no one single correct interpretation of the story, and that is why they are worthwhile to watch and talk about.

Professor Etxabe has leaned into complexity throughout his career: in his academic background, spanning across the world; in his pedagogical style as an Assistant Professor in the Allard School of Law; and in his philosophy towards public scholarship with the Canadian Network of Law & Humanities (CNLH) and as an advisory board member of the Public Humanities Hub. In marrying these two seemingly disparate disciplines, he hopes to communicate to students, peers, and the public that Law and Humanities is an open field, one that encourages multidisciplinary ways of learning and critiquing the law—through movies, literature, philosophy—while also fostering a sense of critical awareness of the structural inequalities, injustices, and violence happening constantly in our polycrisis world.

Professor Etxabe has leaned into complexity throughout his career: in his academic background, spanning across the world; in his pedagogical style as an Assistant Professor in the Allard School of Law; and in his philosophy towards public scholarship with the Canadian Network of Law & Humanities (CNLH) and as an advisory board member of the Public Humanities Hub. In marrying these two seemingly disparate disciplines, he hopes to communicate to students, peers, and the public that Law and Humanities is an open field, one that encourages multidisciplinary ways of learning and critiquing the law—through movies, literature, philosophy—while also fostering a sense of critical awareness of the structural inequalities, injustices, and violence happening constantly in our polycrisis world.

Pushing back against the seemingly inscrutable and intimidating nature of law, Professor Etxabe invites us to put ourselves in the driver’s seat, where our actions, words, ways of relating to one another can make a difference.

The following interview is based on a transcript that has been edited for clarity and length.

Ying Han: What does the public scholarship mean to you?

Julen Etxabe: As a scholar, there is a lot of work that one might have to do in the loneliness of one’s head. However, public scholarship is an important counterweight to the idea that scholarship must be something that we do in the privacy of our own homes, in solitude, in isolation. The way I will frame it feels cliché, but it really is a way of building communities—of getting outside of one’s sense of self, or one sense of discipline and field. Public scholarship is a way of connecting with people, broader society, and the problems of the world. This also includes our own colleagues throughout the institution, especially one as big as UBC, whom we might otherwise never get the opportunity to meet and think together.

YH: I totally agree. In the humanities as well, it often feels like we are just trapped in our own thoughts, not knowing if those thoughts will connect with anyone else. What are some challenges you have faced on this pathway?

JE: I have worked and studied in several different countries, and each institution has its own unique challenges. I come from the Basque Country, completed my PhD at the University of Michigan (U.S.), and then did a postdoctoral fellowship in Finland before coming to UBC. Although I was able to make a lot of friends and connections living within each of these wonderful communities, they are all such different worlds.

It is challenging and time-consuming sometimes to understand the institutional inertia within each context, because those rules are never made explicit. Despite every university now preaching interdisciplinarity and breaking boundaries, it is another story to put into action what can easily be spoken about or written on a website. There are many barriers to doing the type of work that interdisciplinarity requires, even in terms of publications and recognition. To me, those challenges have become ways of also trying to persevere and really pursue the work that I want to do.

CNLH Graduate workshop 2023. Photo courtesy of Emilio Abiusi.

One important thing that I have come to realize when getting situated in different places, is the idea of being open and receptive, but also very generous to one another. We must try to really pay attention to what other people are saying and proposing to you, and to then respond in kind. I have appreciated very much when senior scholars have lent their ears to me, and so I try to reciprocate and do the same with others. That is what unites those experiences in working in an interdisciplinary context: being willing to listen to different ways of seeing the world, and not trying to impose your own perspectives and methodologies. Only then can we collaboratively build the community that we all want to see come to life.

YH: “Reciprocity” is such an important word in the public humanities. What does this term mean to you?

JE: As academics, we have the privilege and the luxury of doing the type of work that is meaningful to us, and so, the idea of reciprocity is to pay back to the society we live in and that sustains our livelihood and our independence. Of course, academic work can be so isolating. There is this tension between, on the one hand, that isolation, which requires us to be a little bit out of step, out of sync, almost living on different temporal coordinates from the day-to-day problems that the community may face. On the other hand, we need to be doing work that the community would actually find useful and important. Reciprocity is a way of trying to find that synchronicity between your needs or your interests as a scholar and responding to the needs of the community. This includes the language you use to communicate why your research is important and other factors of accessibility.

CNLH Inaugural Workshop: Reimagining “the Human” in Research Teaching and Innovation. Photo courtesy of Omri Rozen.

YH: I really liked how you put it as finding a sense of synchronicity. How did this inform the development of the Canadian Network of Law and Humanities (CNLH)?

JE: CNLH is an initiative that has several concurrent and evolving purposes and reasons, coalescing diverse viewpoints. At its core, we began setting up this network to create an opportunity and venue for people to connect with one another within a larger institutional community, but also to express outwardly to the world that this is the work we are doing, that this work matters and should be recognized.

In law school, there is naturally either a professional orientation, or a more academic oriented path, usually towards the social sciences. So, we thought there was a space for bridging law and the humanities, specifically. There are a lot of people within Canada doing this work—they were just not connected to one another. Thus became the idea: to create a glue to bring people together. We do not impose any specific orientation or type of methodology. Most of the people involved come from Allard, but we have also connected with other departments within UBC, and other universities. Our goal is just to be as inclusive as possible.

CNLH Inaugural Workshop 2022

2024 Law, Culture + The Humanities Conference

2024 LCH Graduate Student Workshop

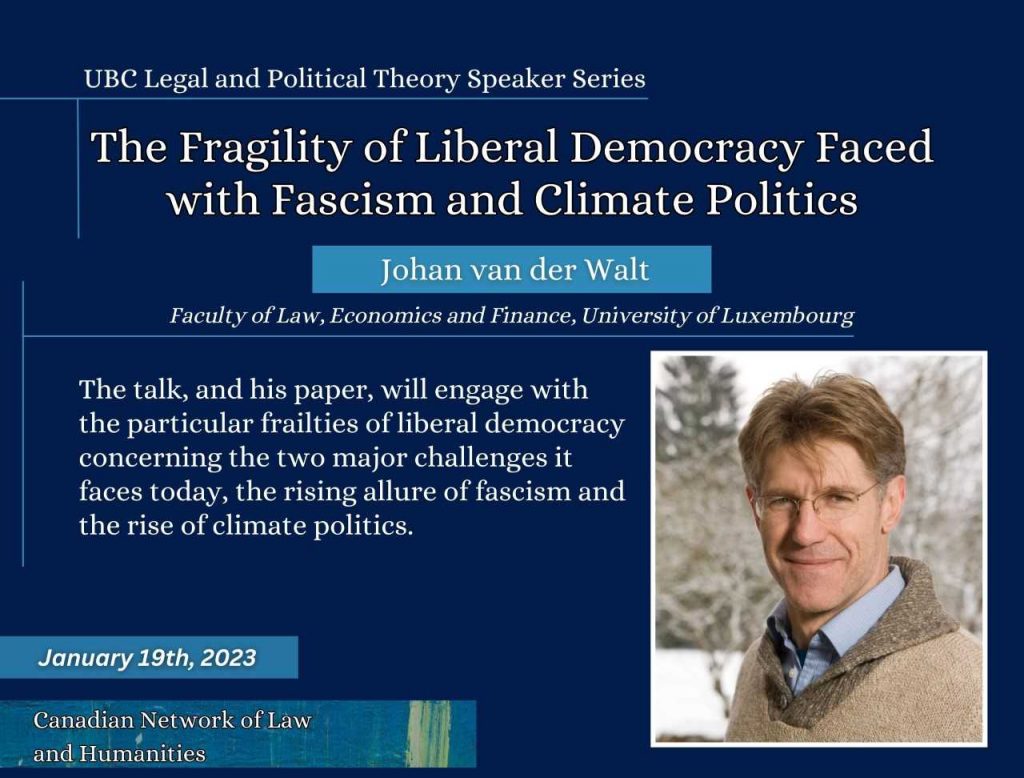

Speaker series hosted with Hoi Kong, Allard professor of constitutional law, through CNLH.

YH: Speaking of different types of public-facing intellectual work, could you share more about your work in human rights?

JE: I consider myself a legal theorist, but my current project has to do with the context of human rights. It is part of my title, the Canada Research Chair in Human Rights. I am studying the reasoning practices of the European Court of Human Rights in comparison with other different courts in the world from a more literary perspective, to bring a new methodology in examining questions of human rights.

It has become the tool that many people use in order to vindicate their claims and make them more audible. I want to understand how the language, how the discourse of human rights is disseminated, translated, and shifts from place to place—as opposed to just a one-dimensional perspective of what human rights are, or even understanding human rights as a sort of imposition from the top. I am more interested in how they come from below and are then utilized in fights in different contexts, for different types of social claims.

YH: Do you find that the more people are exposed to the language of law via the internet and media, that there has been a shifting of language, especially in terms of legal vocabulary entering the everyday lexicon?

JE: This is of course normal because law impinges upon everybody’s lives. The language of law is not something that only privileged people should have access to. Language is always getting translated or vernacularized into different contexts; people apply words and concepts in ways that are useful for their own plights and claims. That is precisely the richness of language: its circulation brings complexity and complications. I would not try to set a pure language of law apart from how some people might wrongly utilize it. In fact, it is important for people to not be afraid of law. Here I quote John Borrows, one of the foremost Indigenous scholars in Canada, who says: Law is not something that is done to you, but it is something that we do. I invited him to give a talk for my students, and he was just a great privilege to have in the class.

John Borrows’s talk on “A Genealogy of Indigenous Law: A Writers Journey.”

YH: Could you speak a little more on indigeneity and law? Have you seen a decolonization of law, especially here in Canada?

JE: One of the things that has made the deepest impression on me since coming to Canada in 2019 is the strength of Indigenous Law and Indigenous communities. As a foreigner, I was interested in, for example, the Quebec secession and the judgments of the Supreme Court, or the civil law tradition versus the common law tradition. However, I was not as aware, if at all, the relationship between Indigenous communities and law. I have really appreciated working with Indigenous scholars and colleagues, learning from how it is that they see the law and how they describe it—the way it forces us to reckon with a very different cosmology, one that upsets inherited, colonial notions of law. As a legal theorist, to me that is terribly exciting: even though it is very, very old—it is also very new.

Methods of decolonization really pose a question to everything we do. It is not something that we can learn by following standards from a book; it is a praxis we must bring to our own work. Sometimes I realize that Canadian politics is not the type of language that I am used to, so I might say the wrong things, however above all, it is important that we pay attention to the communities in which we are working. There is not one right answer; we will sometimes do better, sometimes worse, and sometimes we will fail. Samuel Beckett used to say, we are going to fail but we can learn to fail better. There may be certain pessimism to that, but I do think that it is important for us to not be afraid of mistakes.

Listen to Julen Etxabe on podcast “Bigger Than Me”

YH: That really seems to encapsulate the spirit of collaboration that public scholarship is always about. How has this impacted your pedagogical style?

JE: That is another important aspect of public scholarship: providing opportunities for mentorship for students. I really do aspire for students to get a sense of meaning in their education. I know that they will have lives outside of school, but I want to shape the classroom into an important experience for them as well. On my best days, I want to think that it is an experience that they are not going to want to miss, so I try to bring exciting things to the classroom and make the experience quite participatory for them.

Part of the work that Law and Humanities does as a field is to think of pedagogical tools to bring to the classroom. We might try to think of literature and film as sources of law, as materials that provide a rich arsenal for discussion and thought. In this way, the idea of law as this cold, rule-bound, systematic, frankly boring discipline gets a little bit upset. I sometimes perceive an anxiety that becoming a lawyer entails a losing of the self, and so, I try to bring to the classroom the possibility that you do not have to completely smother those aspects of yourself that make life worth living. I want for the students to get a sense of enchantment, perhaps a sense of, “wow, there is a room for creativity and there is also a place for me in this field.” .

An event we are organizing with Ruth Buchanan from Osgoode Hall Law School is on “Documentary Film and the Law.” I am looking forward to hearing her speak about her experience teaching law and film together. In this class, she has her students create short three-minute documentaries. I am interested in seeing how that type of assessment can be part of the law classroom and thinking about how to implement some of this in my own classroom. [This interview was conducted in late January 2024. Please check out the event page from March 14 here.]

Keep an eye out for upcoming CNLH events here!

YH: As someone who grew up with TV shows like Law and Order being broadcast on repeat, I also have this preconceived notion of what the legal system looks like based on pop culture. How do you communicate ideas within law to a broader audience?

JE: Part of this idea of Law and Humanities is really challenging that preconceived notion of law as an abstract, depersonalized system of rules where individuals do not really matter. My way of talking about law is to make it more like a narrative that people understand or can relate to and have an opinion about. We have, for example, hosted more academic-oriented speaker events among CNLH members, but we have also hosted graduate workshops where we help students develop their own voices as writers or academics, one that can speak to different audiences.

CNLH graduate workshop 2023. Photo courtesy of Emilio Abiusi.

There are not enough opportunities provided within the context of our programs for that type of very specific work, which I find is very necessary and nevertheless lacking. In those contexts, we talk not of law as something that exists somewhat outside of yourself that regulates your life, but something to which you yourself contribute to. If you write in such a bureaucratic manner, then the law that you will then produce or reproduce will be that. So: how can you situate yourself within that context such that law can become more like the law that you would like it to be through your contributions? That is how I approach both pedagogy as well as those events. Law can seem scary and impenetrable, but that should not prevent people from having an opinion that law can hear.

My motto would probably be, do not be afraid of bringing your own mind to the law because that is how law thrives. Law, if it is to be responsive to the society from where it grows, must be able to hear all those voices.

Listen to Julen Etxabe speak more on making law accessible, media literacy, and how he helps foster critical thinking skills in the classroom.

YH: With mass atrocities happening globally, have you seen a shift in the public’s relationship to the law and how people are paying more attention now, especially to human rights issues—for example, South Africa’s genocide case against Israel? What have you seen of your students’ reactions?

JE: As a teacher, for example, you do not really necessarily know exactly what to say in your class or how to even approach the subject. I would not necessarily want to abuse my position as a teacher to say what I think. But I did get feedback from the students who were going through a hard time, who came to talk to me about a certain cynicism and sense of hopelessness about law: what’s the use of law, does it serve anything? How can we be talking about legal theory when the world is burning? This was a very understandable response and good critique of the system.

However, if people are starting to talk about and question the legality of war and bringing cases to court, this must signify that law does matter. It matters how we talk about, define, and name things. Bringing this to the context of my legal theory class, was to then say, okay, it must matter how it is that we theorize law and to examine the lenses by which we observe reality.

So that was my way of having them engage, to not be too despondent or cynical about law, but to think that actually those seemingly abstracted concepts connect directly with our lives. It is my responsibility to show that what we are doing in the class has some relevance to what is going on in the world, that their emotional response is important, and that they can use what we are learning in class to empower themselves.

YH: Thank you for that. Lastly, are there any other projects you are currently working on?

JE: I have just started on another project with scholars working in Hong Kong and Australia. We want to create an Asian Pacific network. Our focus will be thinking about law and literature together as a decolonizing project, looking at marginalized perspectives—not from the metropolis, not from the “Global North.” We do not know exactly what the form will be yet and plan to meet in Hong Kong in March to start thinking about how this might work. It is an interesting and exciting point in a project when you do not always begin with a clear idea. But through collaboration and conversation, you suddenly arrive at exactly what you want it to be. That is what makes a great project, and I am beginning that process now.